Michael great is stepping into the role of Vice President of Architecture, succeeding Murray Jenkins, who was recently named President. As part of the succession plan established by the firm’s founders, this milestone elevation reflects Ankrom Moisan’s commitment to inspiring and empowering people to explore beyond the expected.

Michael Great, Ankrom Moisan’s new Vice President of Architecture.

Starting at Ankrom Moisan as a summer intern in the year 2000, Michael Great has served in various positions throughout the firm and its many studios, including Project Designer, Managing Principal, and, most recently, Design Director of Architecture.

“I had no idea how transformative that first step as a summer intern would be,” he shared. “Each role I’ve had since then has deepened my understanding of design excellence, our various disciplines, and how our business strategy works best when they’re deeply connected. That’s the mindset I’m bringing into this next chapter.”

Knowing the ins and outs of all levels of the firm firsthand, Michael sees his new role as a rare and meaningful opportunity to influence how we design, lead, and evolve.

Empowering Future Design Leaders

Building on our integrated architecture and interiors model, Michael will enhance collaboration across the firm, deepen community engagement, and expand mentorship and professional development opportunities. Investing in people is central to his vision.

One of his first orders of business is to meet with every architect to discuss their hopes, dreams, and visions. He sees it as a way to actively pivot with the industry, moving forward positively while elevating design through our designers.

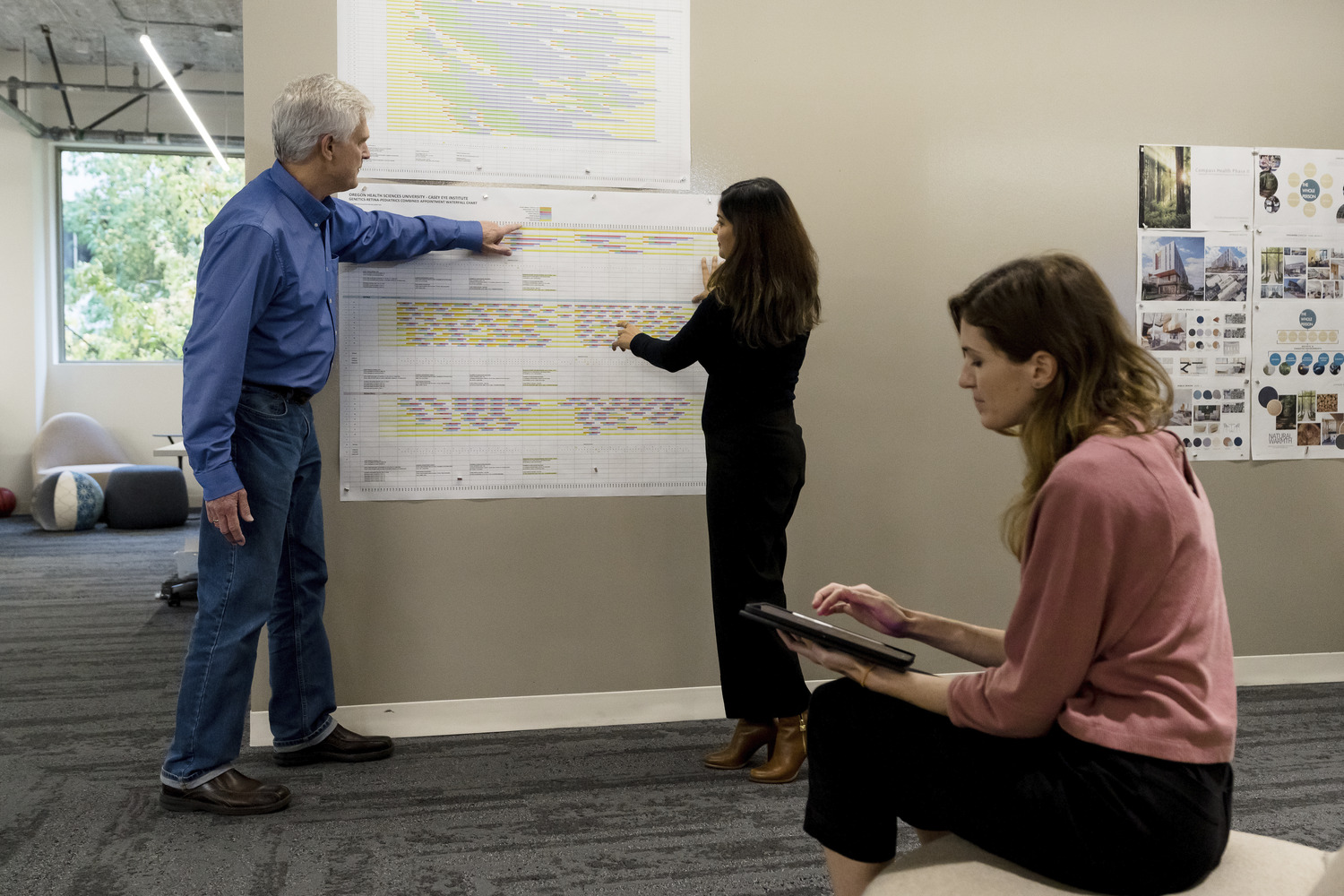

Michael chats with colleagues in the Ankrom Moisan Portland office.

“I want every team member to feel both creatively fulfilled and professionally empowered,” he said. “Trying to make work flows easier for our practice groups and designers is my priority. When people feel supported, they create their best work.”

Michael hopes to support the professional growth of both architects and designers at the firm through mentorship, training, and purpose-built career pathways. “We’re identifying emerging leaders, pairing them with the right guidance, and giving them room to grow. I want to create a culture where people feel inspired and supported every step of the way,” Michael said. “When we do that, great design becomes inevitable.”

“I’m excited to build new systems of support where studio leaders are empowered, mentorship is intentional, and design is consistently elevated,” he said. “What drives me most is shaping a firm culture that champions creativity, accountability, and innovation in equal measure. These values will be the foundation as we continue to grow and redefine the future of Ankrom Moisan.”

Nurturing a Great Design Firm

Michael’s vision for the future of Ankrom Moisan coincides with the firm’s goal of providing great design to our clients, while nurturing a great place to design for our staff. “That’s not just aspirational – it’s operational,” Michael emphasized. By reinforcing design principles, optimizing workflows, and embedding diversity and mentorship across teams, this transition is part of a long-term strategy to strengthen both our creative output and our internal culture.

“My immediate focus is optimizing how we work,” he revealed. “By aligning our project processes with real-time performance insights, we can clearly see where our time is going and how it’s influencing project deliverables. The aim is simple: free up more time for thoughtful, creative design and reduce the burden of repetitive tasks.”

Optimizing Housing Architecture: Leveraging Mass Timber & Sustainable Design

According to Michael, the largest opportunity for optimizing, innovating, and elevating our design work lies within the housing market. “We’re looking at developing a dual-track model that combines bespoke architecture with scalable solutions – leveraging mass timber, modular systems, and a kit-of-parts approach,” he shared. “This allows us to serve both high-design and high-efficiency markets, while maintaining our commitment to sustainability and regional impact to housing needs.”

Michael Great sits at his desk in the Portland office.

Michael’s vision – along with the firm’s vision – for the future is in-line with Murray’s efforts while he served as Vice President of Architecture.

“Murray set a powerful precedent for collaborative leadership and has established many of the foundational systems that the firm relies on today,” Michael reflected. “I plan to build on that legacy by scaling our impact – taking what he’s built and amplifying those systems to support small growth, enhanced creativity, and operational clarity. That’s what this role is about – leading with vision, building momentum, and inviting others to join in a future that’s bold and full of possibility.”

“This isn’t a handoff,” he added. “It’s a progression. And I’m proud to be part of it.”

Relationships are the Cornerstone of Designing Successful Public Projects

Unlike private development, public agency projects often require more time and thoughtful steps at the outset. It’s not that private projects skip these entirely, but the stakes are different: public projects are deeply tied to community trust, transparency, and long-term public value.

Over the years, we’ve found that a strong foundation makes all the difference. Here are three key focus areas we emphasize at the start of any public agency partnership – setting the tone for a collaborative, lasting relationship:

-Establishing Design Expectations & Building Trust

-Defining Guiding Principles

-Engaging the Community Early and Often

Design Expectations = Trust in Action

When kicking off a public agency project, one of the most valuable things you can do is establish trust early – between the ownership team and the design team. That trust starts with clarity around how the design process will unfold, including what’s expected in meetings, how feedback will be gathered, and when key decisions will be made.

A powerful tool in those early conversations? Precedent imagery.

Images of outdoor spaces, interior environments, furniture, building materials, and comparable projects for interiors and exteriors, can help teams express what resonates with them – and just as importantly, what doesn’t. These visual references spark honest conversations and surface values, priorities, and design preferences that might otherwise stay unspoken.

When teams feel comfortable telling us as designers “this doesn’t quite feel like us,” you know you’ve created the kind of collaborative environment where good design thrives.

Harnessing Stakeholder Input: Turning Insights into Actionable Guiding Principles

When our client invited over 800 employees to share their perspectives on project goals and values, it created a powerful opportunity – and a complex challenge:

How do you distill so many voices into a clear, actionable executive summary?

One highly effective method we recommend is the use of a word cloud.

By capturing the most frequently mentioned words and ideas, a word cloud surfaces the priorities that matter most to stakeholders. These guiding principles become a foundation for decision-making, aligning the owner, designer, and construction teams around a common vision.

In our experience, tools like word clouds are critical in early project stages. They translate complex input into focused design drivers, ensuring that stakeholder values are not just heard – they are built into the fabric of the project itself.

Survey responses, interviews, and meeting discussions all offer valuable language that can be mined to create clarity, consensus, and momentum. For SAIF, we started out with this world cloud, and this is how we ended up!

Saif Headquarters

Community Voices: Designing and Inclusive Engagement Process

When working on publicly-funded projects, one thing is always true: you’re not just designing for a client – you’re designing for a community. That comes with both opportunity and responsibility.

Community engagement isn’t just a box to check. It’s a chance to build trust, reflect diverse needs, and ensure public dollars are spent in a way that truly benefits the people who live, work, and move through the community.

But engagement looks different for every client and every community. Some just need you to listen. Others want to inform after the first session or collaborate across several touchpoint. The key is meeting people where they are and providing tools that support informed dialogue.

What should you be prepared to provide the public?

-A clear project overview in everyday language (and possibly in multiple languages)

-Visuals or diagrams that communicate design intent

-A summary of what decisions have been made vs. what’s still open for input

-A way for people to respond – whether it’s in person, online, or through community partners

We’ve learned that when you design the process with care, you end up with stronger outcomes – and stronger relationships.

Passing the Torch

Marking a monumental shift in Ankrom Moisan’s leadership, Vice President of Architecture Murray Jenkins is appointed to become AM’s President, effective July 1st, 2025. As Murray steps into the role currently held by Dave Heater, Dave will transition into a new firm-wide business development role based out of our San Francisco office.

Murray Jenkins and Dave Heater stand outside of Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

Dave’s move, after a decade as President, fulfills a succession plan set in motion by founders Tom Moisan and Stewart Ankrom, who envisioned a firm built to evolve, empower future leaders, and thrive beyond their tenure.

“It is an incredible honor to be entrusted with leading this company,” says Murray. “As President, my goal is to create an environment where our staff feel inspired and empowered, so they can, in turn, inspire our clients through exceptional design and service.”

Bringing 25 years of experience with Ankrom Moisan, having served in every position from Architectural Intern to Vice President of Architecture and Secretary of the Board, Murray’s leadership is distinguished by deep institutional knowledge, a steady hand during transitions, and an unwavering commitment to the firm’s values. His appointment also underscores our employee-owned model – our Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) ensures that every employee has a meaningful stake in the company’s success.

“Murray’s leadership is rooted in our history, and his vision is focused on the future, positioning Ankrom Moisan to continue its track record of design excellence while embracing new opportunities,” said Dave Heater. “Murray’s appointment is the next natural step in our long-term strategy, and I’m confident in his ability to lead the firm into its next chapter.”

Murray along the Portland waterfront, in front of the Ankrom Moisan office

As President, Murray will lead the firm in deepening our expertise across all studios and continuing to expand our leadership in sustainability and mass timber, while exploring strategic opportunities in emerging markets. He also plans to champion innovation across the firm, including the integration of AI and other technologies that will enhance our creativity, efficiency, and impact.

The transition in leadership is centered in Ankrom Moisan’s mission to design places where people and communities thrive. Murray will carry forward Dave’s legacy, maintaining the team structures, operational continuity, and collaborative culture that have shaped the firm’s identity.

With fresh energy and focus, Murray aims to position Ankrom Moisan as a top design firm and model of what excellence, culture, and purpose-driven leadership can look like in the design industry.

“This transition is about community and momentum,” Murray said. “My goal is to grow a resilient firm – one that delivers meaningful design, invests inits people, and rises to meet the challenges of tomorrow. I’m incredibly grateful to Dave for his leadership and the strong foundation he’s built. As we navigate a complex and shifting market, that legacy gives us the clarity and confidence to move forward with purpose.”

Employee Spotlight: 2025 Q1 Employee Ownership Champion Justin Hunt

Recognized as 2025’s Q1 Employee Ownership Champion, Justin Hunt, Senior Technical Designer, is thoughtful, well-spoken, and devotes both his time and energy to supporting the firm however he can.

Coming to Ankrom Moisan 21 years ago (give or take the four years he spent as a part-time design consultant before being brought to the firm full-time), Justin Hunt has always looked out for his teammates.

In grad school at the time, Justin was enrolled at the University of Oregon’s Portland campus. Encountering a power advertising a model-building job, Justin decided to see what it was all about. “I was in the last quarter of grade school, and I love building models, so I thought it would be a good way to get some exposure to a firm I might want to work at, as well as a way to make some extra money before leaving grad school,” he said. “I ended up being the only person that was interviewed, so I got the job.”

“Dave Heater was actually the person who interviewed me – he was a project manager back then and had just made principal,” Justing added. “That was my first time meeting Dave and my first introduction to Ankrom Moisan.”

Justin Hunt in Ankrom Moisan’s Seattle office.

Since his first introduction to the firm, Justin has seen a lot of change, both within Ankrom Moisan and in the architecture industry at large. “Industry-wise, I think the biggest change has been the movement towards digital technologies,” Justin said. “It’s really changed the way we do our work. The way we document and think about projects now has all these digital tools in place to help us visualize them. We don’t make physical models the way we used to anymore, because they’re all digital now.”

“In terms of the office, I would say the biggest thing has been the expansion to multiple states, instead of all being in one location,” he added.

Through these changes, Justin has found the opportunity to grow as well. “I came in as an intern to build models, just a quarter away from finishing graduate school,” he said. “Since then, I’ve grown in basically every way – professionally, technically, and in terms of my presence, ideas, opinions, and maturity, as well.”

Still, Justin feels that there’s so much more to learn. “That’s what. I find so attractive about architecture,” he said. “It’s constantly working on new sites, new cities, new projects, with new clients and new consultants every day.”

Justin’s Reward & Recognition Banner.

Throughout all his time and experience with Ankrom Moisan, Justin has learned a few lessons along the way that he feels are worth sharing. His advice for young professionals just getting their start in the architecture. industry is ‘listen.’ “You can learn from everyone and everything that came before you,” Justin said. “Even though we have all this technology, we’re a profession built on wisdom and knowledge that has been passed down by word of mouth. The lessons learned are documented heavily and instilled in our processes, but listening to the people who experience them is where you can really learn.”

That advice goes to the rest of the firm, too, not just young professionals. “Everyone has something to teach,” Justin continued. “I think it’s just as important for us to hear what new staff have to say, because as soon as we stop listening to what younger people think, we start becoming more isolated and disconnected from what’s really happening in the world.”

Justin also sees a lesson to be had in fostering interpersonal connections and growing those relationships. “I encourage everyone to exercise more empathy in everything you do. Understand the needs of your colleagues, clients, consultants, and contractors, and really understand the factors that are driving them and their motivations,” he said. “As soon as you can empathize with that, you’ll be more successful in incorporating and creating the best project team – and project – possible and just be more successful in general.”

This outlook and consideration for those he works with is one of the reasons that Justin was honored as the first Employee Ownership Champion of 2025.

Justin’s Nomination Video

“To me, employee ownership means representing the firm through my work and doing the best possible job that I can. That’s the way I work every day. It’s just my attitude,” Justin said.

“Someone once told me ‘Do good work.’ I think it was George Signori. I have always listened to that,” Justin continued. “I always try to do good work while being true to the firm’s goals and parameters.”

Now, moving on to the next chapter of his life and career, Justin has had some time to reflect upon his time with Ankrom Moisan. “Most of my favorite memories center around relationships with people at the firm, like holiday parties, soccer games, bike rides, ski trips, cookie exchanges, and the Food Lifeline fundraising events,” he said.

However, the memory that’s most special to Justin comes from his early days with Ankrom Moisan, when he worked in the model shop in the lower annex of our old office. “It was a special crew down there; Jeff Hamilton’s team,” Justin said. “I sat next to Nancy Young and Tania Feliciano, looking out over Vince, Isaac Johnson, Jason Roberts, George Signori, Mike Klein, Jeff Hamilton, Michael Bonn, Dave Heater, and Marc Nordean. They were all dreaming up the future, designing what the city of Portland would look like.”

“It was a golden moment that was really, really special,” he said. “I will never forget what that was like. It inspired me to be the best I could be. I’m super nostalgic about that period of time. Everyone I’ve talked to that was part of that studio at that moment in time has the same feeling. We all knew it was really special.”

Celebrating Our Female Leaders

First kicked off in 2024, the AMasterClass series is an ongoing discussion dedicated to celebrating and sharing the knowledge, insight, and advice accumulated by the female leaders at our firm over the years. They are five-minute-long, miniature crash courses on valuable lessons learned throughout their careers, told in the format of a MasterClass lecture discussion.

An introduction to 2025’s AMasterClass, A Celebration of Female Leaders, shared by Stephanie Hollar.

This year, the three women who opened up to share their experiences with the rest of the firm were Bethanne Mikkelsen, Senior Principal and Office/Retail/Community Studio Co-Leader, Rachel Fazio, Vice President of People, and Alissa Brandt, Vice President of Interiors.

Bethanne, Alissa, and Rachel take part in the live AMasterClass panel in Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

Hosted and moderated by Sheana Hawes, HR Generalist, the three female thought leaders conducted a panel discussion in Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office, sharing their insights, knowledge, and experiences with a live audience, and discussing the similarities between the challenges they face and the lessons they’ve learned from overcoming those challenges.

The graphic from 2025’s AMasterClass event.

Bethanne discussed what it means to be an empathetic leader, sharing that “utilizing these techniques improves team collaboration, increases employee engagement, and enhances communication.”

Rachel shared her perspective on resilient leadership, declaring “you have to build the right mindset for leadership, lead with positivity and humor, and focus on solutions rather than the problem.”

Alissa enlightened us on design-forward leadership, reminding us that inspiration isn’t static – “take time to reflect on what drives you now versus what motivated you at the beginning,” she said. “Let inspiration evolve with your experiences.”

The wisdom shared by Bethanne, Rachel, and Alissa this year – as well as last year’s speakers’ thoughts on Harnessing Your Voice, Being Your Authentic Self, and Solving the Unsolvable – can be viewed in the playlist below.

A playlist of discussions from 2024 and 2025’s AMasterClass series.

Employee Spotlight: 2024 Q4 Employee Ownership Champion Allie Leaf

Having recently returned to work from maternity leave, Allie Leaf has had time to reflect on the wild ride that her career has taken her on so far.

Joining The Society in December 2019, on the cusp of the COVID-19 pandemic, she was encouraged to apply to the hospitality group by her best friend, Dani Richardson, who happened to be working at Ankrom Moisan. “Dani had heard about an opening with The Society and encouraged me to apply,” Allie said. “She said how great they were, and how they planned to grow their team.”

When Allie first started, The Society was in a much different place than it is today. “The team was really small,” she explained.

Allie Leaf

“In a way that was good,” Allie reflected. “It meant I got to be involved with every step and stage of a project, taking it from concept all the way to construction documents, into openings. That allowed me to experience different challenges and learn from each one of them.”

When Allie found out she was recognized as 2024’s Q4 Employee Ownership Champion, it was from the commendation of others. “People started messaging me, saying ‘Congrats, Allie!’ I was like ‘What are you talking about?’ Then I went and watched the nomination video on The Insider.”

Allie’s Nomination Video

“It’s really rewarding to be recognized for my efforts,” she shared. “It’s also so nice to know that some of the headache experiences I went through on certain projects was worth it, and that the challenges were overcome successfully where clients want to work with us again.”

Called out by teammate Alison Gilbo in the nomination video for her “signature attention to detail, patience, and grace,” Allie explains that a sense of humor helps her navigate difficult project challenges, emerging with her head held high. “When things don’t go as planned on a project and it’s out of your control, you could get mad about it, or you could roll with it. I think that having a sense of humor and a willingness to find the best solution, even if it’s not a problem that you created, leads to uncovering the best result for a project.”

Gina Leone, another Society member, also praised Allie’s work ethic and attitude, saying that her leadership, responsibility, and initiative make their team and office a better place to work.

“It’s so flattering that she said that,” Allie shared. “Everyone on our team works so hard; we all bring out the best and have a desire to collaborate and help each other out and help our studio be as great as possible. It’s just the most amazing team.”

Allie’s Society Member Headshot

To Allie, ‘Employee Ownership’ means contributing to the firm’s growth, and helping everyone within it prosper. “I try to own whatever role or task I’m given so that I can contribute the most that I possibly can to our team,” she said. “I’m so proud of the work that we do and how well we all work together, so helping the team any way I can is a great motivator.”

When asked if she had any advice for young professionals who may just be starting their careers, Allie had two pieces of advice to offer:

“Being solution-oriented and tapping into a different part of your creative side – the one that’s more technical and puts the puzzle pieces together – will lead to finding better solutions for the issues you face than dwelling on the negatives.”

The second piece of advice was that emerging design professionals “should explore their creativity and not be afraid to throw big ideas out there.” She added, “You never know if it’ll make it into a project or not, or if there will be something you can gleam from it that will lead to another idea.”

“For Moxy Asheville, I threw out some pretty wild ideas. One of them was this huge, suspended hanging bench in the lobby,” she said, explaining how it happened to her recently. “It’s an iconic moment as guests walk in, and it was all because I thought ‘Hey, this wacky idea just might work!'”

Moxy Asheville’s Suspended Bench

Now that Allie has returned to work, triumphant and celebrated by her teammates, she has gained a new perspective on her place within The Society. She knows that she is supported by her colleagues, that her projects are held in high regard both internally and externally, and she is very excited to continue designing fun, unique projects, seeing where her ‘wacky, wild’ ideas lead her next.

Celebrating AM’s Team Members

Held at the beginning of each year, our annual People Celebration is a time when the firm reflects, looking back at all we have accomplished in the last year and honoring those who have helped to get us where we are. As a part of that celebration, we aim to acknowledge and reward the hard work of the individuals who have really made a difference in the part year.

We are pleased to announce the promotion of 18 team members who have demonstrated a strong commitment to designing smarter and going beyond for their clients and communities.

2025’s Promotion Recipients

Promoted to Senior Director

- Emily Lamunyan – Senior Director of Marketing

Promoted to Studio Co-Leader

- Brad Bane – Affordable Housing Studio Co-Leader

Promoted to Principal

- Cara Godwin – Principal, Operational Excellence, Practice

- Jason Jones – Principal, Higher Education Studio Co-Leader

- Katie Lyslo – Principal, Affordable Housing Studio Co-Leader

- Ashlee Washington – Principal, Healthcare Studio Co-Leader

Promoted to Associate Principal

- Kimberly Gonzales – Associate Principal, Office/Retail/Community

Promoted to Senior Associate

- Aaren DeHaas – Senior Associate, Office/Retail/Community

- Richard Grimes – Senior Associate, Senior Communities

- Alex Kuzmin – Senior Associate, Higher Education

- Jenna Mogstad – Senior Associate, Higher Education

- Scott Soukup – Senior Associate, Senior Communities

- Elisa Zenk, LEED AP BD+C – Senior Associate, Affordable Housing

Promoted to Associate

- Angela Blechschmidt – Associate, The Society

- Sydney Ellison – Associate, Higher Education

- Mandy Housh – Associate, Senior Communities

- Anders O’Neill – Associate, Marketing

Celebrating a culture of leadership, collaboration, and innovation, these promotions recognize individuals who not only push the boundaries of design and expertise, but also foster an environment where mentorship, inclusivity, and creativity thrive.

“Their contributions strengthen our studios, enrich our firm, and shape the future of the communities we serve,” Dave Heater, President, said of the individuals who received promotions this year. “We look forward to the continued impact they will make – both within our teams and in the spaces we create.”

Congratulations to everybody who received a promotion – it is well-deserved, and your hard work is appreciated!

Employee Spotlight: 2024 Q4 Design Champion Monika Araujo

Recognized and honored as Ankrom Moisan’s 2024 Q4 Design Champion, Monika Araujo, Senior Associate, is an active and vital member of her team. In her role as an interior designer, she has made many connections with her coworkers, who constantly support her, encouraging her to grow, learn, and follow what fascinates her.

“I’ve been fortunate to work with some wonderful people here,” she shared. “I enjoy being at Ankrom Moisan because I’m always learning and growing as an interior designer and project manager. My job is always evolving, never stagnant. I can thank Ankrom Moisan for empowering me to pursue my interests.”

Monika’s interests, it seems, revolve around creating well-designed senior communities with her close-knit team, who she credits for the beautiful, impactful work they do. “I find a great team to be key for a successful project. Nurturing relationships over many years develops trust which fosters smooth, efficient, well-designed projects,” Monika said. “I look forward to coming to work every day and having fun with my team. Spending every day with hard-working creatives is a gift.”

Monika on the roof of Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office

“I enjoy being a member of the Senior Communities Studio because we get to design so many types of senior-friendly spaces,” Monika shared. She loves the variety of work that the Senior Communities Studio does, ranging from healthcare and amenities to apartments and offices. “I like doing both renovations and ground-up projects,” she said. “It’s good to have a mix of both.”

Whether it’s for a renovation or a ground-up project, Monika’s favorite aspect of design is the planning process. “I see design as a thoughtful, intentional planning process that leads to the creation and implementation of beautiful, cohesive, functional spaces,” she said. “The cherry on top is seeing people enjoy the spaces we create.”

Seeking inspiration for the thoughtful planning process of design, Monika turns toward nature and the environment around her. “I look for beauty in everyday experiences,” she shared. “Whenever I feel stuck, I go for a walk and spend time away from my desk.”

Monika on top of the Portland office

Since starting at Ankrom Moisan, Monika has grown constantly. “At this stage, I can balance managing multiple projects because I’ve grown professionally every year: learning new skills, maintaining positive relationships, and designing various project types. I have more to learn and experience, and I’m excited to continue my path,” she said.

“I feel a big part of growing professionally is making the time to think and process,” Monika added. “Ankrom Moisan nurtures our well-being in this way so that we can continue to make strides in our profession.

Monika’s nomination video

Called out in her nomination video by Jayne Arnold, Interior Designer, for how organized, approachable, open, and knowledgable she is, Monika explains how she balances the technical, design-oriented aspects of her role with the social relationship building she’s done with clients, excelling at both. “I don’t shy away from learning something new,” Monika revealed. “The more I engage with understanding all the work that goes into building spaces, including the architectural, consultant, and contractors’ work, the more I have to offer our clients during design and construction meetings.”

Alissa Brandt, Vice President of Interiors, also quite literally sang Monika’s praise, highlighting how Monika is a mentor to the rest of the Senior Communities team and always brings her best. That element of mentorship is something that Monika values greatly, “I enjoy mentoring other designers. I’ve had many mentors in my career that have helped me along my path. My advice to new design professionals is to seek out a mentor,” said Monika. “Secondly, also aim to improve yourself. Take classes, attend events, visit places, and listen to clients.”

When she learned that she was one of 2024’s Q4 Reward & Recognition Champions, Monika took a moment to acknowledge that her efforts do not exist in a vacuum, and that her team is a big influence on how she approaches her work. “It feels great to be recognized, of course. I’m lucky to work with such a talented team that shares a similar vision to work hard and create beautiful, functional spaces.”

Thinking about how the Reward & Recognition program will continue to honor the efforts of Ankrom Moisan Employees in the future, Monika reflected on how important it is that hard work is both recognized and celebrated. “It’s important to recognize people so they feel they are an integral part of AM,” she said. “I hope the legacy of the program will be that we keep honoring our teammates over the years, so they feel valued.”

Mass Timber Case Study: Sandy Pine

As a firm, Ankrom Moisan has a robust experience with mass timber. We were early adopters of the technology, and our expertise exemplifies our commitment to both sustainability and innovation.

Initially, we carved out a niche in mass timber office buildings, completing several projects with technologies like CLT, NLT, and Mass Plywood systems.

As our expertise and relationships in the mass timber market grew, we decided to merge this knowledge with our core strength in multifamily housing. With over 33,000 residential units completed for developers over the past 40+ years, we have amassed a deep understanding of this typology.

Seeing an opportunity for technology to meet typology, we decided it was time to unify and evolve these two distinct areas of expertise.

Sandy Pine stands as a testament to this evolution – a towering high-rise of market-rate housing in Portland, Oregon’s vibrant east side. This project represents many of our best strategies for integrating modular CLT mass timber systems within multifamily buildings, offering a perfect case study for the future of mass timber in housing projects of various types.

Check out the case study here:

Employee Spotlight: 2024 Q3 Design Champion Feature Aaren DeHaas

Honorerd as the Q3 Design Champion for Ankrom Moisan’s Reward & Recognition Program, Aaron DeHaas relies upon the support of her team to organize chaos and deliver exceptional workplace designs that speak to the goals and culture of her clients.

Aaren in Ankrom Moisan’s Seattle office

Attracted to Ankrom Moisan by the caliber and variety of project types being done here, Aaron has been a part of the workplace team for the last nine years. Finding opportunities to learn and grow is very important to her, so she naturally has flourished within her team.

“The workplace team is a really fast-paced group,” she said. “We go through a ton of projects in a year and have such a strong, supportive team. It’s interesting because we have such a great variety of projects and scale, from itty bitty projects where the client just wants to add a wall and a door, to full buildings.”

“We work on a lot of projects at once,” Aaron said. “At one point I was working on 12 projects at the same time. It’s a lot but you’re getting experience in every phase of a project at once. It almost expedites your learning in a way, since you’re going through the workflows from start to finish on a project in various scales. It’s on-the-job learning.”

While having to juggle so many projects at a time could easily become overwhelming, Aaren says that the workplace team supports each other in a way that reduces the amount of stress she feels.

“There’s a collaborative nature that’s always apparent and always somebody to turn to that’s got your back,” said Aaron. Whatever it is, we all band together to make sure anything that needs to get done is completed. Having team members you can rely on and trust has been the most supportive thing to me and my success.”

Aaren’s recognition banner

Aaren’s favorite projects are the fully designed projects where there is an opportunity for her to let loose and flex her creative design muscles. These projects are often on-of-a-kind. “Because each client’s culture is different, you can kind of tailor those project to reflect those cultures,” she said. “I get inspired by that kind of connection with clients and with using their cultures and personalities to guide me in design. It’s fun to take their brand personality – their colors and fonts and signage and that sort of thing – and transform it into a tangible space. There’s always bumps along the way, but once you get it, it feels great. Clients like it too because you understand them, and they feel heard.”

Aaren in Ankrom Moisan’s Seattle office

When she first found out about her recognition as 2024’s third Design Champion, Aaron was shocked. “I found out from the videos in Green Screen In Between. I was completely surprised,” she said. “I saw my picture and did a triple take. It took a little bit to sink in.” Now that she’s acclimated to the honor, she has high hopes for the future of the Rewards & Recognition program, although she is still humble about her selection as an honoree. “It feels really nice to be recognized. It’s a nice thing to do for people and I hope that this program encourages people to continue to grow and put out their best work,” she said. “Although I’m the one being honored, you can’t do what I do without the rest of the workplace team and the supportive structure we have,” she added. “It’s too much to do by yourself.”

Aaren’s Rewards & Recognition Nomination Video

In her nomination video, Alissa Brandt, Vice President of Interiors, praised Aaren for her ability to manage complex, high-pressure projects while delivering exceptional results, as well as your tendency to meet demanding deadlines with creative solutions while still finding the time to guide and support her teammates. Acknowledging that she can’t keep everything in her head, nor would she want to, Aaren explained how she uses notes to stay organized and on top of her work, sharing important information with her team in a timely manner.

“I’ve heard it called ‘organized chaos,” she said. “I’m organized and have a system that works for me. I have so many notepads and sticky notes everywhere; I’m not sure if it works for anyone else.”

Bethanne Mikkelsen, Senior Principle, similarly calls our Aaren in her nomination video, complimenting her ability to elevate the design process and facilitate a creative culture that thrives within the firm.

“As far as elevating design,” Aaren responds, “I think it goes back to taking risks. You can’t find the full potential of what a design could be without putting yourself out there a little bit. I try to understand who a client is and what their culture is like, and how to push it a little further; How we can take their comfort zone and push it to the next level.”

This is something that Aaren could do over and over again. “I feel that design is never done,” she confessed. “It’s almost like its own organism, always changing and adapting. I think that that kind of flexibility is really important – you can get to a point where you’re happy with where a design is, but you have to be open to the possibility of making adjustments. Inspiration can hit at any moment and your design may be better for it in the end.”

“As long as our clients are happy, that’s what our goal is – that they have a comfortable space that shows off who they are and attracts the talent they’re looking for,” she said. “it’s all about making good designs that reflect our clients and their goals.”